8 Steps for Great Professional Development

Have you ever participated in any professional development training that you thought was great? The best training you have had in ages, but then couldn’t find time to apply what you learned. Newsflash, that was a great event, one part of the Professional Development Journey. Professional Development (PD), not to be confused with training, is always associated with change. The purpose of PD is to develop awareness, knowledge, dispositions and/or skills with the intent to move from some current state to an envisioned future state. Orchestrating that move is known as Change Management, of which training is only a small part.

Great PD is Part of Change Management.

The field of Change Management is mostly associated with organizational change and was popularized by John Kotter in the 1990’s with his 8 stage process for leading change. Within the educational context we have Michael Fullan’s 8 Forces for Change. 8 seems to be the magic number when trying to change something. But, whether it be 8 stages or 8 forces, one thing holds true in all Change Management processes, training plays a small part and at that, it comes very late in the process. Strict adherence to Change Management as a process is crucial for effecting any change, regardless if the change is personal to your practice or in service of an initiative for your school. It is for this reason, when planning any PD, we must always be mindful of these stages:

Stage 1 - It all begins with the question Why? Why is this change important? Why do I/we need to change? Kotter wants to light a fire in the organization and Fullen wants you to make your Moral purpose explicit so you can be constantly reminded of why you are investing precious time and resources for professional growth.

Stage 2 - Change is about people. So, you better get the right people ‘on the bus’ from the start. Start building the capacity for change by identifying early the people that can remove barriers and support learning so that we can realize that envisioned future state.

Stage 3 - Speaking of that envisioned future state, with the right people engaged from the very beginning you can craft a motivating and empowering vision to begin getting buy-in from the wider organization. Buy-in is critical to the learning journey and will ensure the right mindset when the learning begins.

Stage 4 - You need to write a compelling narrative for change that learning communities understand and can easily retell to each other. A narrative, supported by guiding policies, that establishes what we want our learning communities to achieve, as well as how they can do it.

Stage 5 - Remove barriers to change. Note we haven’t even begun training yet. What’s the point of developing capacity if we leave in place obstacles that will impede our staff’s ability to apply learning and new skills.

Stage 6 - Finally, we can begin training, but start small with the leadership and ensure they get some good early wins. Alignment is often the greatest win at this stage.

Stage 7 - TRAIN TRAIN TRAIN and ramp up the communications to share what is being learned and how it is being implemented. This is when the culture of an organization starts to shift.

Stage 8 - Consolidate your victories and institutionalize them. This requires a great deal of coordination and energy to cause a significant shift in the organization.

So, to have great PD, you need to do a lot of work up front. To have great virtual PD, requires the same process, but the actual training requires twice the amount of time to plan the facilitation as there is much more scripting involved, especially with how to encourage engagement and interaction. An upside, though, once you embrace virtual PD, and the tools that enable it, you create significant efficiencies to move through the initial stages of change much more quickly.

Great PD begins with the question, ‘Why?’. There is no easy way to answer this. The ‘why’ is often something we see and feel, but we struggle to put a name on it. Sometimes in our rush to label it from our own perspective, we do so in a way that limits our ability to influence others, as we communicate this need for change from our own perspective. Most educational leaders, and leaders in general, struggle to articulate the need for change. They struggle because they are often alone, or in very insular groups, when identifying and conceptualizing the need for change.

The Importance Of A Good Diagnosis

Great PD starts with an honest diagnosis, which then feeds into the Change Management process. In fact, the product of moving through the first 3 stages of change should be an honest diagnosis that compels and guides people to act. Many leaders, though, only skim the surface when it comes to developing a diagnosis. They limit their diagnosis to the obvious and often frame it as some aspiration, something to ‘reach for’. They shortcut Stage 1 by largely relying on assumptions and move too quickly into Stage 3. To develop good diagnoses we need leaders that can call attention to a few critical factors that not only address deficiencies, but also when addressed will act as pivot points to multiply the effectiveness of effort.

To illustrate this point of why we can’t have good PD without a good diagnosis I will refer to Richard Rumelt’s Strategic Planning model from his book, Good Strategy / Bad Strategy: The Difference and Why It Matters. Rumelt’s model for creating good strategy he calls the kernel:

The kernel of a strategy contains three elements: a diagnosis, a guiding policy, and coherent action. The guiding policy specifies the approach to dealing with the obstacles called out in the diagnosis...Coherent actions are feasible coordinated policies, resource commitments, and actions designed to carry out the guiding policy

The kernel aligns with every stage for change management. As alluded to above, stages 1-3 produce the diagnosis, stages 4-5 are where guiding policies are developed and communicated and stages 6-8 ensure coherent action. This is no coincidence that these models are so compatible, as they are based on decades of documented best practice, going back as far as the 1950’s. Furthermore, both models are human-centered. Change fails more often than not, not necessarily because of people, but because we don’t plan with people in mind.

A good diagnosis begins with a simple, yet honest observation: "...my humanity and that of the people close to me has been elevated in ways that I haven't fully processed. My youngest daughter, who is a 2nd grader, has been clinging to me in ways that feel natural and good, and are also different from our pre-COVID-19 reality and all of our hustle-bustle. All three of my children seem more at peace and joyful in this new phase, which really provokes for me additional interrogation of our education system with particular focus on the student and family experience." Dr. Cheryl Camacho, the Chief of the South Bend Empowerment Zone in South Bend, Indiana, expressed this sentiment in a recent Forbes article on how educational leaders of color are responding to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Dr. Camacho now needs to distil her observation, and subsequent interrogation, into a simple narrative that calls attention to the critical factors. Her honest appraisal has also identified pivot points, students and family, that if can be leveraged, will multiply the effectiveness of effort to effect change. This is the start of the diagnosis, an honest acknowledgement that simplifies the overwhelming complexity of reality. This developing diagnosis also has moral purpose, it calls attention to the impact on families. As this diagnosis develops it will dramatically influence what type of training is needed, for whom and how change will be evidenced.

4 Questions to Guide Great Professional Development

The most honest joke I hear in workshops is when I introduce Rick DuFour’s 4 Professional Learning Community questions as a model for planning teacher PD. When I ask teachers to replace the word ‘student’ with ‘teacher’ it often provokes a few laughs, followed by, “why shouldn’t we expect that what contributes to effective teaching and learning for students would also follow for teachers”. Furthermore, DuFour’s questions are intended to seed interdependence within learning communities, which is also critical in planning great PD. Great PD, especially when student learning is the focus, should never be a solo initiative. For this reason, educators need to ask these four questions of each other:

What do we want all teachers to know and be able to do?

How will we know if they are able to apply that knowledge and demonstrate those capabilities?

How will we respond when some teachers do not demonstrate understanding and application of the knowledge and skills central to our school’s pedagogical beliefs?

How will we extend learning for teachers who are already proficient?

These questions are great tools for navigating Stages 6 and 7 of the change management process. Collaboratively answering these questions will make explicit the dispositions and behaviours we seek as a result of the training before there is any training. It’s not the result that we should focus on, but what the people who are critical to realising that result need to do. At a minimum, if sufficient time is invested on the first two questions, where the diagnosis is the lens for exploring these questions, the impact of PD will be greatly improved. These questions also set the stage for devising guiding policies that will inform teams on what they need to know and do, as well as how it will be evaluated, thus empowering them to identify their own training needs and take ownership of their PD. As teams start to align with the guiding policies, which ensures coherence in action across teaching teams, administrators can begin exploring questions 3 and 4, which the latter question begins to shift attention to Stage 8, consolidating and building on successful change.

Finally, We Can Start Learning

Renee Rehfeldt, a good friend, and colleague, outlined these four strategies as a way to categorize the numerous ways we can train staff, all of which can be facilitated virtually with the same or greater impact compared to face-to-face:

INTERNAL PROFESSIONAL LEARNING

Teacher to teacher or staff to staff; conducted by the school for the school staff and guided by the school’s needs; i.e., PLCs, observations, book clubs, contracted facilitators (in-service PD), and mentoring.

NETWORK PROFESSIONAL LEARNING

School to school (or multiple schools); organized by schools for schools, guided by what each school needs; i.e., job-a-likes, school visits, contracted facilitators (shared cost), and conferences with staff facilitating.

EXTERNAL PROFESSIONAL LEARNING

Provided by an outside organization or specialist and provides an external certification; i.e., public registration workshops, conferences with professionals facilitating and visiting consultants.

PERSONAL LEARNING NETWORK

Coordinated by the individual for their own needs, interests, and professional growth; likely to involve other professionals; i.e., self-directed learning and online learning.

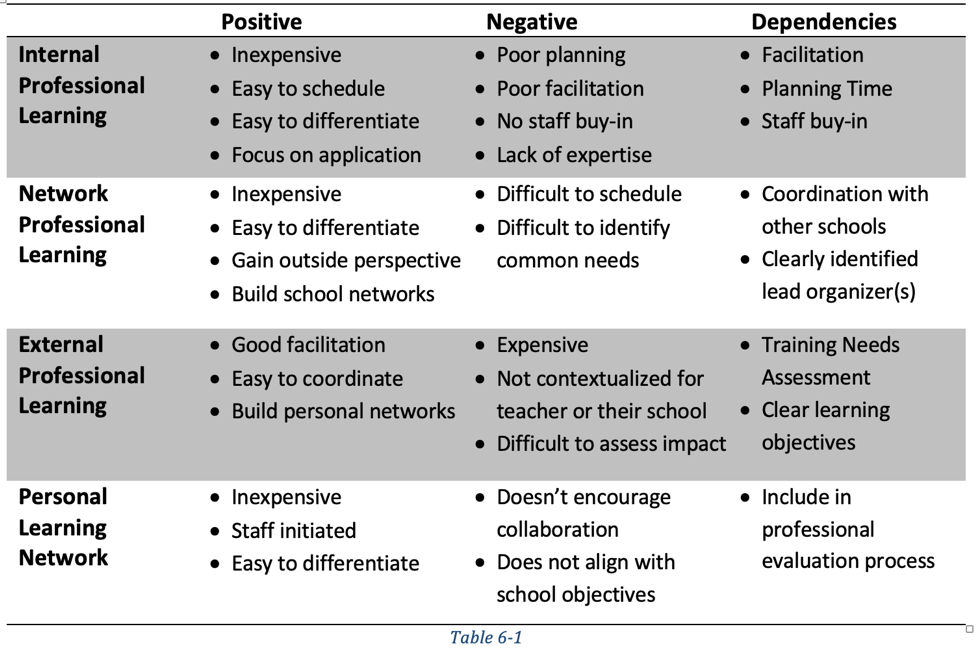

As highlighted in the table below, each strategy has a variety of positive and negative attributes that Renee and I have observed across hundreds of schools. These attributes are by no means a hard and fast rule and there are many exceptions, but they tend to be typical when there is no full-time PD Coordinator. Additionally, common areas of concern that schools need to consider for all four strategies are: (1) participant learning needs aren’t formally assessed or surveyed in advance, (2) staff aren’t held accountable to any learning objectives, and (3) there are no tools to evaluate the application of learning. In the table, I also try to highlight some dependencies, as in what is required to ensure the PD is effective for that respective strategy.

Leaders that are assigned the role of coordinating PD often have full-time teaching or administrative responsibilities, and in addition to a lack of time also have budgetary and resource constraints. For this reason, they are normally limited to one of the four strategies for professional learning, with internal professional learning being the most commonly employed strategy. An additional obstacle to coordinating effective PD is that PD Coordinators limit the scope of their role to specified periods of time, PD Days, which hinders staff from effectively scaffolding professional learning. PD days could be utilized more effectively if more time was allotted to plan productive sessions, which should include revisiting and bridging to past content as well as ensuring facilitators are well prepared. Unfortunately, though, these PD periods often devolve into unproductive discussions about work or are used to catch up on work. The greatest limitation of the most commonly used form of PD is the inability to demonstrate good leadership, evidenced by thoughtful planning and strong facilitation skills.

What I propose, and have been very successful in implementing with schools over the past years, is a hybrid approach to utilizing all 4 strategies, aligned to practical learning objectives that I hold senior leaders accountable to understand and assess. Over the years I have learned, as an administrator and training provider, that whatever I can’t do for lack of time or knowledge, I can outsource. This said, outsourcing comes at a high cost, so I can’t outsource everything. Many schools, unfortunately, take an all-or-nothing approach to developing their middle leaders, either by sending them to very expensive programs or not training them at all. The latter is justified by the belief they will learn on the job. The former fails to realize desired outcomes even though you pay a high cost because an environment isn’t created to apply what is learned; administrative and structural obstacles are left unaddressed within the school. The hybrid option for developing middle leadership capacity requires every stakeholder involved in the process to be held accountable:

SENIOR LEADERS: Ensure buy-in, assess needs, provide networking opportunities, mentor middle leaders and assess the impact of learning.

STAFF: Demonstrate agency by seeking out additional resources to deepen understanding of relevant content, demonstrate the application, reflect and hone new skills.

FACILITATORS: Clearly communicate learning objectives, create interactive learning environments, understand participants learning goals and provide tools to assess applications.

The hybrid approach, when bolstered by all stakeholders being held accountable to the objective of capacity-building staff, will prove to be the most effective. A simple example using all four professional learning strategies will look like this:

INTERNAL PROFESSIONAL LEARNING

Have cohorts meet to assess needs and identify training options;

Provide time off the table to ‘in-house experts’ and instructional coaches to facilitate knowledge and experience sharing; and

Contract professional facilitators to virtually present and ‘set the scene’ for change. These facilitators, when not limited by ‘PD Days’ or travel budgets, can differentiate their messaging and instruction for staff at different stages of development, as well as scaffold their instruction to promote job-embedded learning.

EXTERNAL PROFESSIONAL LEARNING

Nominate or invite staff to enroll for open registration programs in groups of 2-4 per division; and

Staff participating in outside workshops should present key learnings to colleagues.

NETWORKED PROFESSIONAL LEARNING

Encourage staff to host job-a-likes with peers in other schools to explore specific topics relevant to their stage of professional development; and

Staff can connect with peers in other schools through curriculum-based online networks or Facebook to identify and explore teaching and learning inquiries.

PERSONAL LEARNING NETWORKS

Encourage staff to document their journey and publish it in relevant forums;

Supplement the purchase of literature and online courses with the expectation that recipients of school funding will present key findings to colleagues; and

Encourage action learning projects bolstered by personal research.

Geat PD Needs To Be Embedded

Great PD is not an event, it’s a journey. Along this journey we visit many places in search of knowledge, expose ourselves to new perspectives, share with others what we have learned, and demonstrate how this journey has contributed to our growth. Stages 1-3 of the Change Management process is meant to provide guidance on how we need people within our organization to grow. Stages 4-5 are necessary to help our community understand and align with the vision for change. Stages 6-7 are when we begin to engage and shape the learning journey for everyone within our organization. But, change can still fail if we stop short of ensuring the dispositions and skills are embedded in the day-to-day work of every staff member. This latter stage will consume the greatest amount of energy and attention of senior leadership, but will also be the most rewarding.

A well-documented and thoroughly researched professional development strategy is the 70-20-10 model of leadership development, where research has shown that 70% of leadership development comes from on-the-job work experience. 20% is support provided by superiors or coaches, and 10% is formal structured learning. However, for on-the-job experience to be an effective form of PD, senior leaders need to understand the requisite capacity that must be developed so that they can monitor and provide support as needed, which is largely what the 20% entails. This model, although less researched in other areas of development, anecdotally is the most effective model for job-embedded PD.

An important consideration to understand to ensure the 70-20-10 model is effectively executed is that of time. Proportionally, structured learning would appear to have a very small role, such as external workshops, conferences, and diploma programs. However, they play a significant role in the beginning, as this is where the seeds for development are planted and if professional learning is to flourish, then senior leaders need to create an environment ripe for growth, that is regularly tended to. Opportunities to apply content require a large amount of support from senior leaders. It will take time for staff to process all the new information. During this period senior leaders are reaffirming the learning objectives and helping staff to understand the new content within their school context. In the beginning, senior leaders have a larger role. Over time though, as staff becomes more effective at seeking out learning opportunities, reflecting on what they are learning, and honing their new knowledge and skills through application, the pro- portions take their proper shape.

Developing staff capacity, in parallel with attending to regular work responsibilities, is a long process. In fact, it is a life-long process. The 70-20-10 model for developing capacity is the most effective process. There is tremendous front loading that must take place before teachers can act agentically in terms of their own PD. This model utilizes the positive attributes of all four professional learning strategies, emphasizes application, and makes the role of all relevant stakeholders clear. The key to this model that not only makes it effective but also sustainable, is the regular engagement with peers and senior leadership. Truly great PD not only ensures access to the resources we need to grow but has us regularly interacting with peers and leadership along the way.